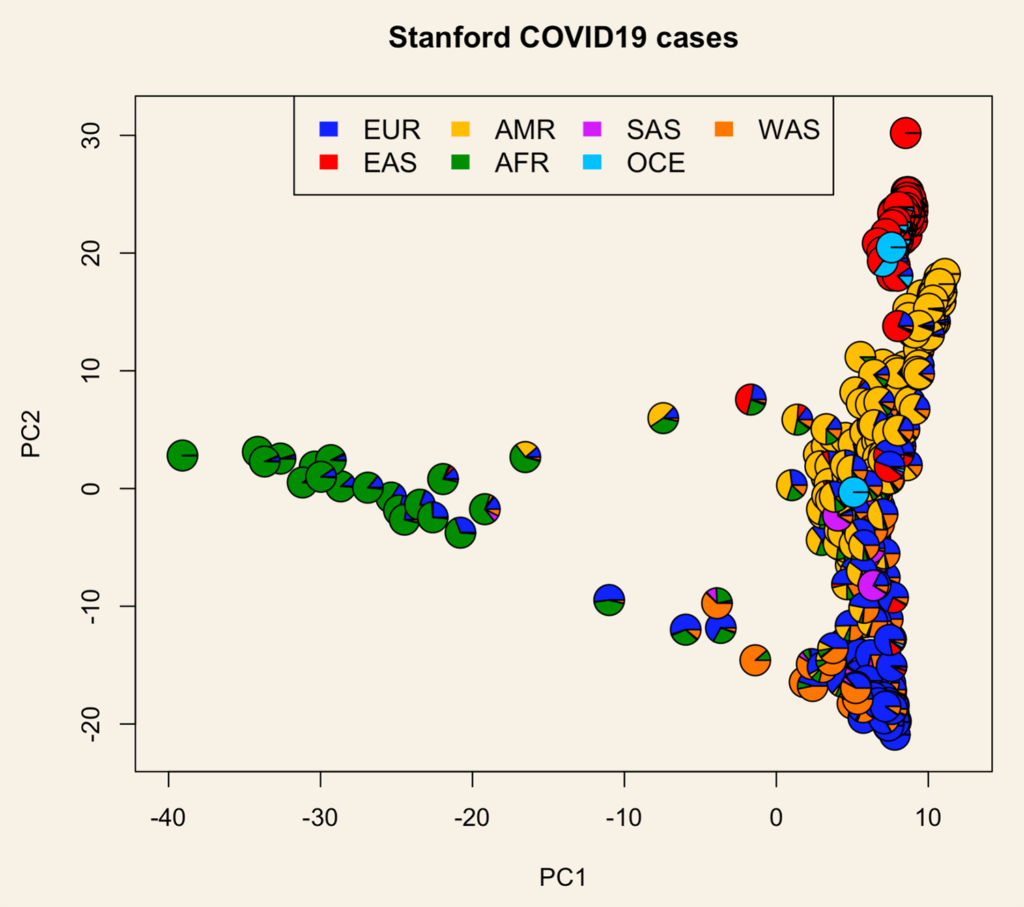

Genetics could explain why some people get severe COVID-19. During the pandemic we researched the genetic predisposition to COVID-19 severity. In a matter of a few months we built a biobank at Stanford University. The majority of individuals were admixed individuals, i.e. of multiple ancestries. I’m really amazed as to how quickly we were able to put together a biobank to study a deadly pandemic. To read more about the Stanford Biobank for COVID-19 please see link here.

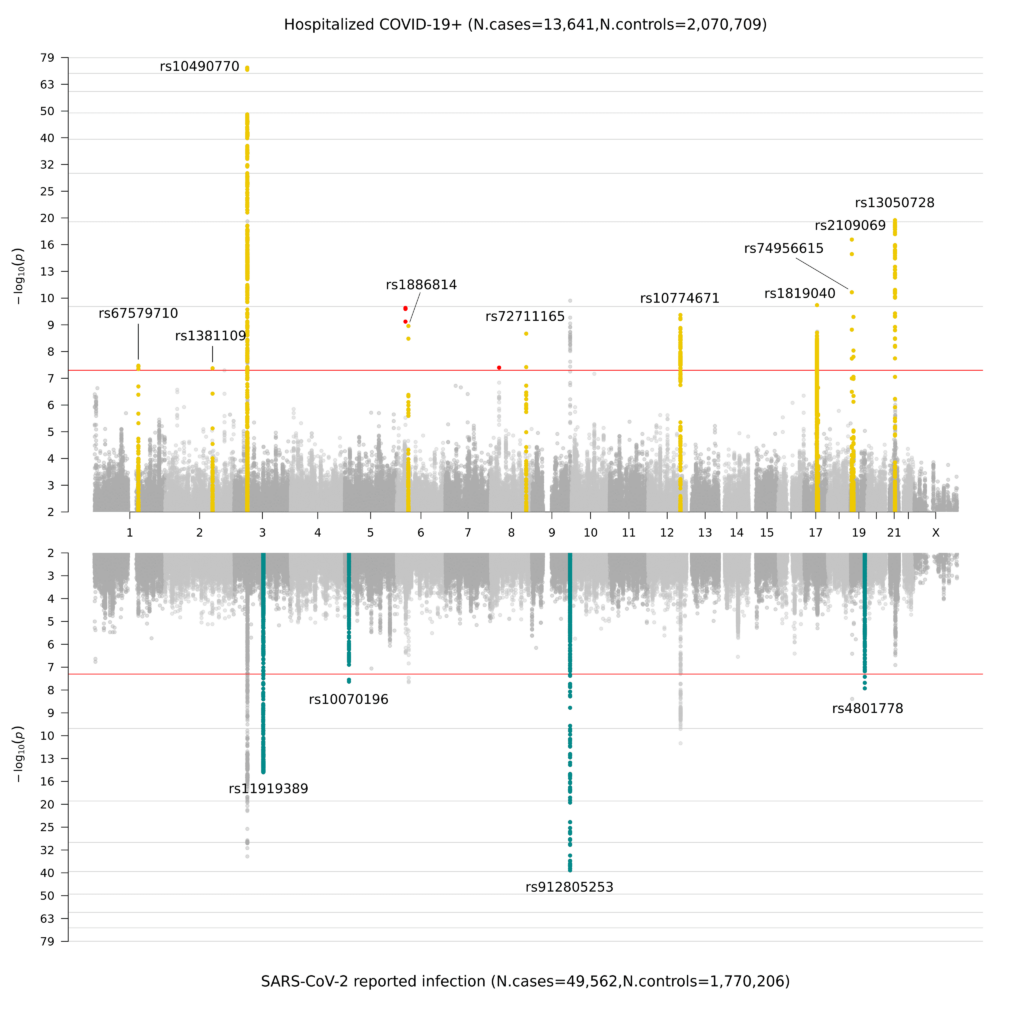

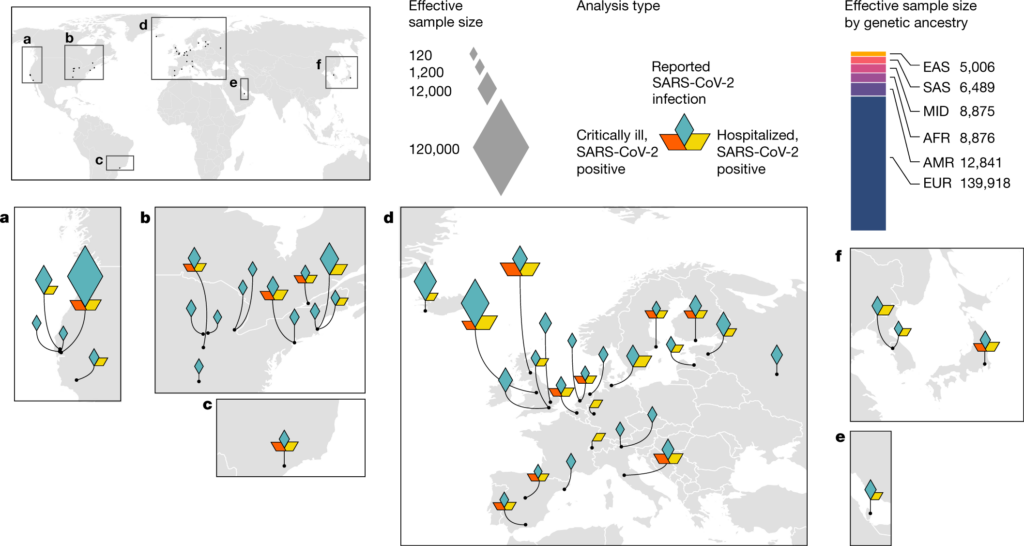

With our international colleagues and collaborators we were able to put together results across biobanks and conduct an international meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 (virus) infection and COVID-19 (disease) severity.

Location of the international COVID-19 biobanks.

This resulted in over 40 loci associated SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 hospitalization. Paper summarizing findings is found in Nature.